Mission: Impossible (film)

| Mission: Impossible | |

|---|---|

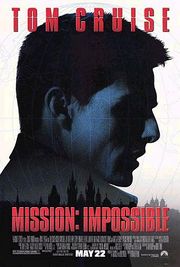

Promotional poster |

|

| Directed by | Brian De Palma |

| Produced by | Paul Hitchcock Tom Cruise Elias Badra Paula Wagner |

| Screenplay by | David Koepp Robert Towne |

| Story by | David Koepp Steven Zaillian |

| Starring | Tom Cruise Emmanuelle Béart Kristin Scott Thomas Jon Voight Jean Reno Ving Rhames Vanessa Redgrave |

| Music by | Danny Elfman Main Theme: Lalo Schifrin |

| Cinematography | Stephen H. Burum |

| Editing by | Paul Hirsch |

| Studio | Paramount Pictures Cruise/Wagner |

| Distributed by | United StatesParamount Pictures Non-United States United International Pictures |

| Release date(s) | June 6, 1996 |

| Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English French |

| Budget | $80,000,000 |

| Gross revenue | $457,696,359 (worldwide) |

| Followed by | Mission: Impossible II |

Mission: Impossible is a 1996 action thriller directed by Brian De Palma and starring Tom Cruise as Ethan Hunt. The plot follows Hunt's mission to uncover the mole within the CIA who has framed him for the murders of his entire IMF team. Work on the script had begun early with filmmaker Sydney Pollack on board, before De Palma, Steven Zaillian, David Koepp, and Robert Towne were brought in. In fact, the film went into pre-production without a shooting script. De Palma came up with some action sequences, but neither Koepp nor Towne were satisfied with the story that leads up to these events.

U2 band members Larry Mullen Jr. and Adam Clayton produced their own version of the original theme song. The song went into top ten charts around the world and was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance. The movie was the third highest grossing of the year. It is the first movie based on the television series of the same name and was followed by two sequels, Mission: Impossible II (2000) and Mission: Impossible III (2006).

Contents |

Plot

Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) is an agent of an Impossible Missions Force (IMF) team, an unofficial branch of the CIA. Led by Jim Phelps (Jon Voight), the team assembles for a mission in Prague to prevent an American diplomat from selling the non-official cover (NOC) list, a comprehensive list of all covert agents in Eastern Europe. The mission goes hopelessly wrong, seemingly resulting in the death of every team member except Hunt. Fleeing the scene, Hunt meets with IMF Director Eugene Kittridge (Henry Czerny) at a café. Kittridge discloses that operation was a setup meant to draw out a mole in the IMF named "Job" who has made a deal to sell the list to an arms dealer known as "Max." Suspicion now falls on Hunt, the only survivor of the mission, who makes a daring escape from the café and flees into the city.

Hunt returns to the IMF safe house, where he discovers that fellow agent Claire Phelps (Emmanuelle Béart), Jim's wife, has survived the mission. Hunt begins email correspondence with Max (Vanessa Redgrave) and meets with her in person to warn her about the fake NOC list—and offers to deliver the real one in exchange for $10 million and a face-to-face meeting with Job. Max agrees and Hunt assembles a team of disavowed agents: computer expert Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames) and pilot Franz Krieger (Jean Reno). Hunt, Stickell, Krieger, and Claire infiltrate the heavily fortified CIA headquarters in Langley and successfully steal the full NOC list before escaping to a safe house in London. There, Hunt discovers that his uncle and mother have been falsely arrested for drug trafficking in an attempt by Kittridge to lure him out of hiding. This infuriates Hunt, and he contacts Kittridge, who offers to drop the charges when Hunt surrenders. Hunt stays on the line long enough for Kittridge to trace him to London, then hangs up to find Jim Phelps standing right next to him.

Phelps, presumed dead in the Prague operation, tells Hunt that Kittridge is the mole and is trying to tie up loose ends. Hunt listens, mentally piecing together the operation and realizing that Phelps himself is Job. Hunt pretends to accept the story, understanding that Krieger has assisted Phelps, but is still doubtful about Claire's place in the conspiracy.

The next day, Max and Hunt arrange to meet aboard the TGV en route to Paris, with Claire and Stickell aboard to provide backup. Kittridge is also aboard, having received tickets and a watch from Hunt. Aboard the train, Hunt delivers the NOC list to Max, who directs him to the baggage car to find his money and Job. Claire arrives in the baggage car to meet with Phelps, revealing her complicity as she suggests that they leave with the money and let Ethan take the blame. "Jim" suddenly peels his face away, revealing himself as Hunt in disguise. They are interrupted by the arrival of the real Phelps: unhinged, armed and demanding that Hunt hand over the money. Hunt does so, but then slowly puts on a pair of glasses from the original operation in Prague, with a camera built into the bridge. The image of Phelps, alive, is transmitted to the video watch carried by Kittridge, exposing Job's true identity.

Claire tries to intervene, and Phelps kills her instead and climbs up to the roof of the car, while Krieger approaches the moving train in a helicopter to extract him. Hunt follows him onto the roof, impeding him and tethering Krieger's helicopter to the train, dragging it into the Channel Tunnel. In the tunnel, Phelps leaps to the helicopter. Hunt follows, climbing the helicopter's landing skids and attaching explosive chewing gum, a final relic of Prague, to the windshield. He leaps back to the train just as the ensuing explosion kills Phelps and Krieger.

Now with custody of the NOC list, Max, and Job's true identity, Kittridge reinstates Stickell and drops his investigation against Hunt, who resigns from the IMF. As he flies home, a flight attendant approaches him and asks, through a coded phrase, if he is ready to take on a new mission.

Cast

- Tom Cruise as Ethan Hunt

- Jon Voight as Jim Phelps

- Emmanuelle Béart as Claire Phelps

- Henry Czerny as Eugene Kittridge

- Jean Reno as Franz Krieger

- Ving Rhames as Luther Stickell

- Kristin Scott Thomas as Sarah Davies

- Vanessa Redgrave as Max

- Emilio Estevez as Jack (uncredited)

- Ingeborga Dapkunaite as Hannah

- Karel Dobrý as Matthias

Production

Paramount Pictures owned the rights to the television series and had tried for years to make a film version but had failed to come up with a viable treatment. Tom Cruise was a fan of the show since he was young and thought that it would be a good idea for a film.[1] The actor chose Mission: Impossible to be the first project of his new production company and convinced Paramount to put up a $70 million budget.[2] Cruise and his producing partner Paula Wagner worked on a story with filmmaker Sydney Pollack for a few months when the actor hired Brian De Palma to direct.[3] They went through two screenplay drafts that no one liked. De Palma brought in screenwriters Steve Zaillian, David Koepp, and finally Robert Towne. According to the director, the goal of the script was to "constantly surprise the audience".[3] Reportedly, Koepp was paid $1 million to rewrite an original script by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz. According to one project source, there were problems with dialogue and story development. However, the basic plot remained intact.[4]

The film went into pre-production without a script that the filmmakers wanted to use.[3] De Palma designed the action sequences but neither Koepp or Towne were satisfied with the story that would make these sequences take place. Towne ended up helping organize a beginning, middle and end to hang story details on while De Palma and Koepp worked on the plot.[3] De Palma convinced Cruise to set the first act of the film in Prague, a city rarely seen in Hollywood films at the time.[2] Reportedly, studio executives wanted to keep the film's budget in the $40–50 million range, but Cruise wanted a "big, showy action piece" that took the budget up to the $62 million range.[4] The scene that takes place in a glass-walled restaurant with a big lobster tank in the middle and three huge fish tanks overhead was Cruise's idea.[2] There were 16 tons in all of the tanks and there was a concern that when they blew, a lot of glass would fly around. De Palma tried the sequence with a stuntman but it did not look convincing and he asked Cruise to do it despite the possibility that the actor could have drowned.[2]

The script that Cruise approved called for a final showdown to take place on top of a moving train. The actor wanted to use the famously fast French train the TGV[2] but rail authorities did not want any part of the stunt performed on their trains.[3] When that was no longer a problem, the track was not available. De Palma visited railroads on two continents trying to get permission.[3] Cruise took the train owners out to dinner and the next day they were allowed to use it.[2] For the actual sequence, the actor wanted wind that was so powerful that it could knock him off the train. Cruise had difficulty finding the right machine that would create the wind velocity that would look visually accurate before remembering a simulator he used while training as a skydiver. The only machine of its kind in Europe was located and acquired. Cruise had it produce winds up to 140 miles per hour so it would distort his face.[2] Most of the sequence, however, was filmed on a stage against a blue screen for later digitizing by the visual effects team at Industrial Light & Magic.[5]

The filmmakers delivered the film on time and under budget with Cruise doing most of his own stunts.[1] Initially, there was a sophisticated opening sequence that introduced a love triangle between Phelps, his wife and Ethan Hunt that was removed because it took the test audience "out of the genre", according to De Palma.[3] There were rumors that the actor and De Palma did not get along and they were fueled by the director excusing himself at the last moment from scheduled media interviews before the film's theatrical release.[1]

Apple Computer had a $15 million promotion linked to the film that included a game, print ads and television spot featuring scenes from the TV show turned into the feature film; dealer and in-theater promos; and a placement of Apple personal computers in the film. This was an attempt on Apple's part to improve their image after posting a $740 million loss in its fiscal second quarter.[6]

Reaction

Original cast

Actor Greg Morris, who portrayed Barney Collier in the original television series, was reportedly disgusted with the film's treatment of the Phelps character and he walked out of the theater before the film ended.[7] Martin Landau, who portrayed Rollin Hand in the original series, was equally negative concerning the film. In an MTV interview in October 2009, Laundau stated: "When they were working on an early incarnation of the first one – not the script they ultimately did – they wanted the entire team to be destroyed, done away with one at a time, and I was against that," he said. "It was basically an action-adventure movie and not 'Mission.' 'Mission' was a mind game. The ideal mission was getting in and getting out without anyone ever knowing we were there. So the whole texture changed. Why volunteer to essentially have our characters commit suicide? I passed on it. The script wasn't that good either."[8]

Box office

Mission: Impossible opened on May 22, 1996 in 3,012 theaters—the most ever up to that point—and broke the record for a film opening on Wednesday with US$11.8 million, beating the $11.7 million Terminator 2 made in 1991.[9] The film also set house records in several theaters around the United States.[10] Mission: Impossible grossed $75 million in its first six days, surpassing the previous record holder, Jurassic Park and took in more than $56 million over the four-day Memorial Day weekend, beating out previous record holder, The Flintstones.[11] Cruise deferred his usual $20 million fee for a significant percentage of the box office.[11] The film went on to make $180.9 million in North America and $276.7 million in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $457.6 million.[12]

Reviews

Despite the large revenues, the film received a mixed reaction from critics and has a 56% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a 60 metascore for Metacritic. Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, "This is a movie that exists in the instant, and we must exist in the instant to enjoy it".[13] In his review for the New York Times, Stephen Holden addressed the film's convoluted plot: "If that story doesn't make a shred of sense on any number of levels, so what? Neither did the television series, in which basic credibility didn't matter so long as its sci-fi popular mechanics kept up the suspense".[14] USA Today gave the film three out of four stars and said that it was "stylish, brisk but lacking in human dimension despite an attractive cast, the glass is either half-empty or half-full here, though the concoction goes down with ease".[15] However, Hal Hinson, in his review for the Washington Post, wrote, "There are empty thrills, and some suspense. But throughout the film, we keep waiting for some trace of personality, some color in the dialogue, some hipness in the staging or in the characters' attitudes. And it's not there".[16] Time magazine's Richard Schickel wrote, "What is not present in Mission: Impossible (which, aside from the title, sound-track quotations from the theme song and self-destructing assignment tapes, has little to do with the old TV show) is a plot that logically links all these events or characters with any discernible motives beyond surviving the crisis of the moment".[17] Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B" rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, "The problem isn't that the plot is too complicated; it's that each detail is given the exact same nagging emphasis. Intriguing yet mechanistic, jammed with action yet as talky and dense as a physics seminar, the studiously labyrinthine Mission: Impossible grabs your attention without quite tickling your imagination".[18]

Additionally, many fans of the TV series were disappointed —and even angered— at the major character change of eternal "good guy" Jim Phelps into a traitor and a murderer.

The film's usage of thieves, each with a skill needed for the heist, was seen by some as lifted directly from previous movies, such as the film noir Rififi.[19]

Music

Incidental score

This film utilizes the original Lalo Schifrin television theme music. However, originally Alan Silvestri was earmarked to do the incidental music and had, in fact, recorded somewhere around 23 minutes of the score. During post production, due to creative differences, Silvestri's music was rejected and replaced by new music by composer Danny Elfman. Silvestri's music does exist and bootlegs of this have been released on CD. In addition, clips of the film with the original Silvestri score in appropriate places are available on the Internet.[20]

Score album

-

-

-

- Note: This section does NOT refer to the Mission: Impossible OST.

-

-

Point Music released a CD of Elfman's score on June 28, 1996. (Some cues are also included on the song album.)

- Sleeping Beauty (2:28)

- Mission: Impossible Theme - Lalo Schifrin (1:02)

- Red Handed (4:21)

- Big Trouble (5:33)

- Love Theme? (2:21)

- Mole Hunt (3:02)

- The Disc (1:54)

- Max Found (1:02)

- Looking For "Job" (4:38)

- Betrayal (2:46)

- The Heist (5:46)

- Uh-Oh! (1:28)

- Biblical Revelation (1:33)

- Phone Home (2:25)

- Train Time (4:11)

- Menage a Trois (2:55)

- Zoom A (1:53)

- Zoom B (2:54)

Theme song

U2 bandmates Larry Mullen Jr. and Adam Clayton were fans of the TV show and knew the original theme song well, but were nervous about remaking Lalo Schifrin's legendary theme song.[21] Clayton put together his own version in New York City and Mullen did his in Dublin on weekends between U2 recording sessions. The two musicians were influenced by Brian Eno and the European dance club scene sound of the recently finished album Passengers. They allowed Polygram to pick its favorite and they wanted both. In a month, they had two versions of the song and five remixed by DJs. All seven tracks appeared on a limited edition vinyl release.[21]

The song went to the top 10 on charts around the world, was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance in 1997, and was a definite critical and commercial success.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Portman, Jamie (May 18, 1996). "Cruise's Mission Accomplished". Montreal Gazette: pp. E3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Penfield III, Wilder (May 19, 1996). "The Impossible Dream". Toronto Sun: pp. S3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Green, Tom (May 22, 1996). "Handling an Impossible Task". USA Today: pp. 1D.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brennan, Judy (December 16, 1995). "Cruise's Mission". Entertainment Weekly.

- ↑ Wolff, Ellen (May 22, 1996). "Mission Uses Sound of Silence". Variety.

- ↑ Enrico, Dottie (April 30, 1996). "Apple's Mission: Hollywood Computer Ads Take New Turn". USA Today: pp. 4B.

- ↑ 'Mission: Impossible' TV stars disgruntled, CNN, May 29, 1996

- ↑ Martin Landau Discusses 'Mission: Impossible' Movies, MTV Movies Blog, October 29, 2009

- ↑ Thomas, Karen (May 24, 1996). "Mission is Successful, Breaks Wednesday Record". USA Today: pp. 1D.

- ↑ Hindes, Andrew (May 24, 1996). "Mission Cruises to B.O. Record". Variety: pp. 1.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Weinraub, Bernard (May 28, 1996). "Cruise's Thriller Breaking Records". New York Times: pp. 15.

- ↑ "Mission: Impossible". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=missionimpossible.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (May 31, 1996). "Mission: Impossible". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19960531/REVIEWS/605310305/1023. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (May 22, 1996). "Mission: Impossible". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/library/filmarchive/mission_impossible.html. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ Clark, Mike (May 22, 1996). "Should You Decide to Accept It, Plot Works". USA Today: pp. 1D.

- ↑ Hinson, Hal (May 22, 1996). "De Palma's Mission Implausible". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/missionimpossible.htm#hinson. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (May 27, 1996). "Movie: Improbable". Time. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,984610,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (May 31, 1996). "Mission: Impossible". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,292824,00.html. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ Luther, Claudia (April 1, 2008). "Blacklisted Director Jules Dassin Dies at 96". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2008/apr/01/local/me-dassin1. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ↑ YouTube: Climactic train scene with the original Alan Silvestri score

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Gunderson, Edna (May 15, 1996). "U2 Members on a Mission Remix". USA Today: pp. 12D.

External links

- Mission: Impossible at the Internet Movie Database

- Mission: Impossible at TomCruise.com

- Mission: Impossible at Allmovie

- Mission: Impossible at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mission: Impossible at Metacritic

- Mission: Impossible at Box Office Mojo

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||